Madden 2009 is finally out and with it, Electronic Arts is celebrating Madden’s twentieth anniversary as the most successful and one of the longest running video game franchises in history. But Madden’s history is a tale of uphill battles against better, more innovative games, which it has triumphed over time and time again thanks to blitz marketing, industry manhandling, and the coup de grace, an exclusive NFL license. Let’s look back at all the good times.

1988: John Madden Football

This was the first game in the series. I never played it and know very little about it. According to Wikipedia, due to graphical limitations, there were only six players on the field per team. Let’s move on.

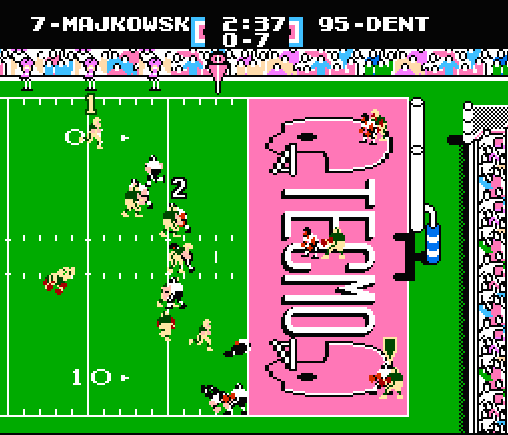

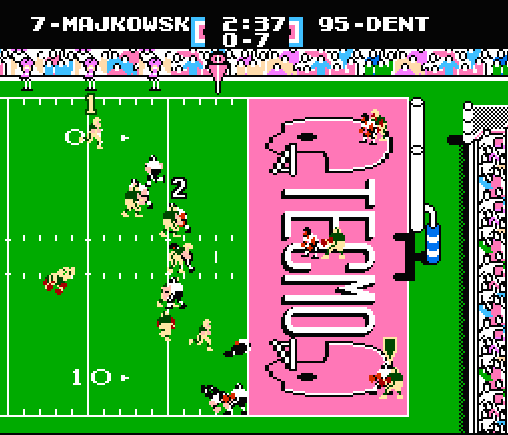

1989: The Japanese make one hell of a football game

Tecmo Bowl for the NES was the first popular football game franchise. The gameplay was simplistic and the original game lacked a real license but it was fun as hell. Tecmo Super Bowl for the Super NES added a real license and was even better than the original. Tecmo has gone on to make Dead or Alive Beach Volleyball, because they’re from Japan, and they can do whatever they wanted without being judged.

1993: Turns out people would rather play with real teams and player names

The Madden series’ greatest contribution to sports video games will be its use of a full league license. Madden ’94 was the first football game with real players and teams, and while this may seem a trivial detail, it made the game more engaging, more fun, but more importantly it opened the floodgates for sports fans who could finally play with their favorite teams. Players were no longer playing with a generic team from San Francisco in a generic football league, but were controlling Joe Montana and taking the 49ers to the Super Bowl. Electronic Arts and Madden are one of the main reasons video games are as popular as they are today.

Not to trivialize the Madden series, the Sega Genesis era marked the golden days for both the Madden series and EA Sports in general. Their games were the most fun, had the best graphics and sold the most. On a side note, NHL ’94 might still be the best sports game (and drinking game) ever.

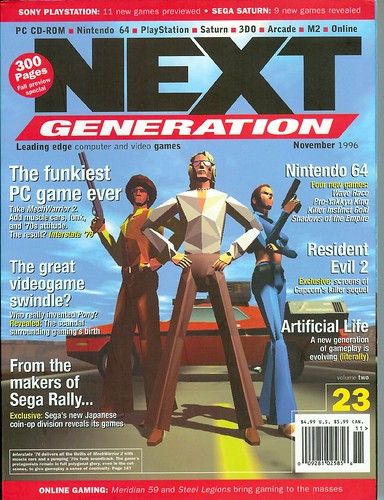

1997: Gameday '98 makes the jump to polygons

More realistic than Madden, Sony’s NFL Gameday outsold Madden for three consecutive years, making it the only sports game in the US to dethrone Madden as best selling sports game. While Gameday ‘97 was a great game, ‘98 was not only the first 3D football game, it made an incredibly successful transition on its first try. The controls were tight, the animations lifelike and fluid, all while retaining its fun. Madden soon made the jump to 3D (though not as smoothly), adopted some of Gameday’s features and soon the Sony series began its decent into the abyss with less and less successful updates.

More realistic than Madden, Sony’s NFL Gameday outsold Madden for three consecutive years, making it the only sports game in the US to dethrone Madden as best selling sports game. While Gameday ‘97 was a great game, ‘98 was not only the first 3D football game, it made an incredibly successful transition on its first try. The controls were tight, the animations lifelike and fluid, all while retaining its fun. Madden soon made the jump to 3D (though not as smoothly), adopted some of Gameday’s features and soon the Sony series began its decent into the abyss with less and less successful updates.

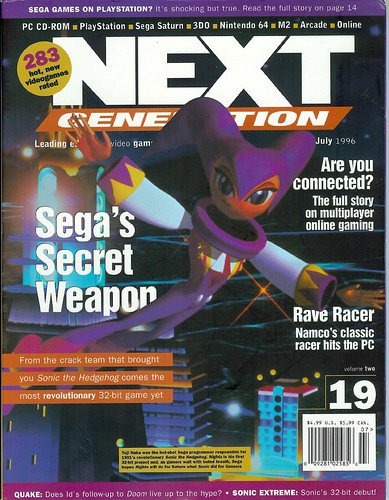

Late nineties: the Dark Ages

The late nineties were a dark age for the Madden games. Gameday was superior, while Madden was struggling to make the jump to 3D, with overly simplistic gameplay, bad motion capturing implementation (once a move was initiated you had to wait until the animation was completed for the next action to take place) and dumb as fuck or cheap as hell artificial intelligence. This is not to mention the money plays that especially plagued the game’s multiplayer. Still, Madden sold well (as always) and it was ultimately the lack of Madden that broke the camel’s back, and killed the Sega Saturn (the most underappreciated console in history).

1999: NFL 2K sets a new high water mark for sports games

NFL 2K was made from scratch by the relatively unknown Visual Concepts. It was a launch title for the new Sega Dreamcast. Madden wasn’t coming to the system so the stakes were high and chance of success low. But Visual Concepts killed it. NFL 2K was the true next gen football experience; even this year’s Madden ’09 is nothing more than a slightly more polished, prettier take on NFL 2K with new rosters.

NFL 2K was made from scratch by the relatively unknown Visual Concepts. It was a launch title for the new Sega Dreamcast. Madden wasn’t coming to the system so the stakes were high and chance of success low. But Visual Concepts killed it. NFL 2K was the true next gen football experience; even this year’s Madden ’09 is nothing more than a slightly more polished, prettier take on NFL 2K with new rosters.

NFL 2K revolutionized motion capture use, using an unprecedented 20,000 motion captured moves to created fluid, lifelike animation. The graphics were amazing, and coupled with the game’s TV quality presentation, the game could easily be mistaken for a television broadcast. The gameplay was the real draw, however. Amazingly responsive controls, a great physics and collision detection engine and truly realistic AI made this gaem the first realistic portrayal of football in a videogame. For the remainder of my days, NFL 2K will be the only time I hear the sounds two and kay muttered together without cringing.

2000: The rebirth of Madden

Electronic Arts put a lot of blood, sweat and tears into revitalizing the series. Madden 2001, for the Playstaion 2, was an excellent sports game, on par and perhaps superior in some respects to NFL 2K1 on the Dreamcast. The graphics were beautiful, controls and AI were massively overhauled and the production values set a new benchmark, even surpassing NFL 2K’s. The next few years would mark a bitter war between the two for best football (sports?) game.

Electronic Arts put a lot of blood, sweat and tears into revitalizing the series. Madden 2001, for the Playstaion 2, was an excellent sports game, on par and perhaps superior in some respects to NFL 2K1 on the Dreamcast. The graphics were beautiful, controls and AI were massively overhauled and the production values set a new benchmark, even surpassing NFL 2K’s. The next few years would mark a bitter war between the two for best football (sports?) game.

2005: Electronic Arts gets exclusive NFL license

In 2005, Electronic Arts signed an exclusive licensing agreement (originally running through 2009, but now extended to 2012), making the Madden franchise the only video game with official player and team names. This was the final death blow to all of Madden’s remaining competition (basically Sega’s NFL 2K series). A sports game is useless without real player names (thanks to its game play, light years ahead of Fifa’s, Winning Eleven for the Playstation is the only example of a successful sports game franchise lacking a license).

Madden is now the only name left in town when it comes to football games. They could pack each copy with nothing more than John Madden’s air locked fart and it would still break a million copies.

I've been playing NHL 08 like every day and reading the Hipster Runoff a bunch recently and their take on the whole "alt/authentic/popular/mainstream" complex. Which got me thinking about how video games have become the entertainment option of choice for dudebags over the years.

I've been playing NHL 08 like every day and reading the Hipster Runoff a bunch recently and their take on the whole "alt/authentic/popular/mainstream" complex. Which got me thinking about how video games have become the entertainment option of choice for dudebags over the years.