Next Generation was a video game magazine ahead of its time (still ahead of its time?). If Electronic Gaming Monthly was Hello! Magazine, Next Generation was The New York Times Book Review. Next Generation tried to analyze where the video game industry was headed, why new games were important, and what new ground they broke – other than just cooler graphics and better controls.

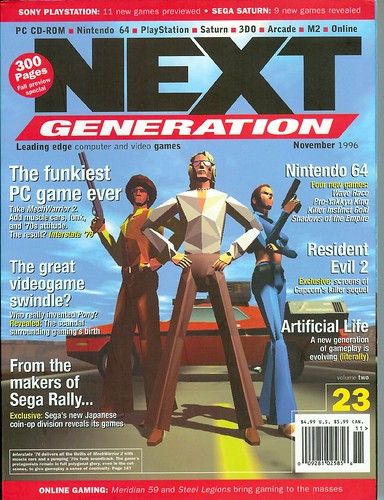

Next Generation regularly drew parallels with other art forms and aspired to be more than just another video game magazine. It was printed on high gloss paper, had a very clean minimalist presentation and was the first video game magazine to run longform interviews and show half page and full page screenshots. It treated games as art and crafted its magazine to the highest standards; editorially, visually and physically.

Next Generation showed how video games could be art and it covered the burgeoning industry with intelligence and wit, even though it was easy to see how some may have regarded it as boring or snooty. Next Generation didn’t limit itself to basic questions about new characters, release dates, rumored projects and favorite pizza toppings when it interviewed game designers, programmers and executives. It asked where the industry was going. What they admired about other game developers. How their game was breaking new ground. In a column entitled “The Way Games Should Be”, game developers reflected on game design’s current state and where it needed to be taken.

It rated games on a five star scale, like one rates a movie or a music album. Five stars were awarded very rarely, only to games which approached perfection or broke important new ground. Metal Gear Solid was awarded five stars for setting a new high water mark in storytelling. Super Mario 64 received five stars for nearly perfecting the user controls and camera of 3D gaming, still in its infancy. Video game reviews are usually on a ten point scale, with one decimal point precision. This epitomizes the childishness of video game journalism, and the industry as a whole. Only a child would say he is seven and three quarters; and only a video game reviewer could give a game a 6.7.

Chuck Klosterman, writing for Esquire in 2006 (read it online), speculated that the reason video game critiques didn’t exist yet (at least in North America, maybe they do in Japan), was because video games, as interactive mediums, explore the consequences of free will and the myriad of potentialities that ensue. As he put it, what if Gone with the Wind ended differently for every person; with a bear attack, with Scarlett killing Rhett, or Rhett coming back inside the house (“Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn. Not!”). Video game criticism doesn’t exist because it can’t get started.

This is an important observation, but the reason video game criticism, and high brow video game journalism don’t exist is due to a more fundamental problem. Next Generation failed was because it served a very peculiar niche. It was an intelligent, high brow video game magazine. The problem was (still is?) that most video game players were in a state of perpetual adolescence (at least vis a vis videogames) and most intellectuals regard video games as nothing more than glorified, high tech board games.

The arguments put out to show video games as art do more harm than good. Journalists and company representatives quote the number of artists who worked on a game, how deep and complex a game’s storyline is or how beautifully composed its score is. These are all valid arguments as to why a video game may be considered artful but fail to illustrate the most important element of a video game’s art: the experience.

No one will deny that film is an art form. Many movies have beautiful scores, great storylines, and well written dialogue; but the distinguishing factor in a film’s art is the visual. A movie can express certain things through the camera’s lens better than any book, opera or painting. It is the same for video games.

skate (written with a lower case “s” to accentuate its alternativeness) is a skateboarding game released by one of the biggest video game publishers in the industry; Electronic Arts. It was released last year to glowing reviews and strong sales yet everyone missed the point as to why the game was so important. It was the first extreme sports game to forego a detached from reality arcade experience for a realistic simulation. The Tony Hawk series of games were incredibly fun but unrealistic and failed to get across the authentic experience of skateboarding. The goal of the game (and other copy cat extreme sports games) was to string dozens of tricks together in a combo chain where the score increased exponentially the longer the chain. In the final level of Tony Hawk 2, I managed to pull off a 2.4 million point combo; which is absurdly high compared to my first level combos in the one to two thousand point range. While this was incredibly fun, it failed to articulate the genuine experience of skateboarding, which is the patience and hard work of executing these tricks which were being chained together like a candy necklace; no regard for the individual elements and only a vague notion of what the whole resembles.

While there are point challenges in skate, that isn’t the game’s main focus. Instead, the game reverts to simplicity and is about completing complex tricks with style. When I first began playing, I could barely ollie (skateboard lingo for a jump) properly. Through patience and repetition (and wall punching), I slowly grew accustomed to the controls and began performing more complex tricks, ollying higher and chaining tricks together. This was all accomplished without leveling up my character, increasing the character’s abilities on a point based scale. In this sense, I was becoming a more talented skater in a more natural, lifelike way.

The real question is: Do hardcore gamers want to read this kind of analysis? It’s hard to say. Maybe because no one has offered this kind of analysis, gamers themselves don’t know if they want to read this sort of thing. An even more difficult question to answer is whether the casual, mainstream video game player wants to read this sort of thing? Many mainstream gamers play video games solely as a distraction, and hence are looking for art and refinement neither from their games nor from their video game journalism. But some casual gamers (like the very talented filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro who praises Silent Hill’s visuals and likens it to the work of David Lynch) might not only appreciate this sort of analysis, but look at video games in a new light.

No comments:

Post a Comment